A traditional and prescribed burn is a deliberately set and carefully controlled fire. Fire-dependent ecosystems, such as Black Oak savannahs, contain rare native prairie plants that respond positively to burning and grow more vigorously. These burns are a part of the City’s long-term management plan to restore and protect rare Black Oak woodlands and savannahs in Toronto’s High Park, South Humber Park and Lambton Park.

Previously referred to as a “prescribed” burn, it is now referenced as a “traditional and prescribed” burn in order to use more accurate wording to honour the traditional practice of Indigenous people on Turtle Island.

The City of Toronto is currently preparing for a traditional and prescribed burn (Biinaakzigewok Anishnaabeg) in High Park and South Humber Park. The burn is scheduled to take place in early 2025 and is dependent on favourable weather conditions. Collaboration with the Indigenous Land Stewardship Circle will bring Indigenous ceremony and traditional knowledge to the centre of this year’s burn.

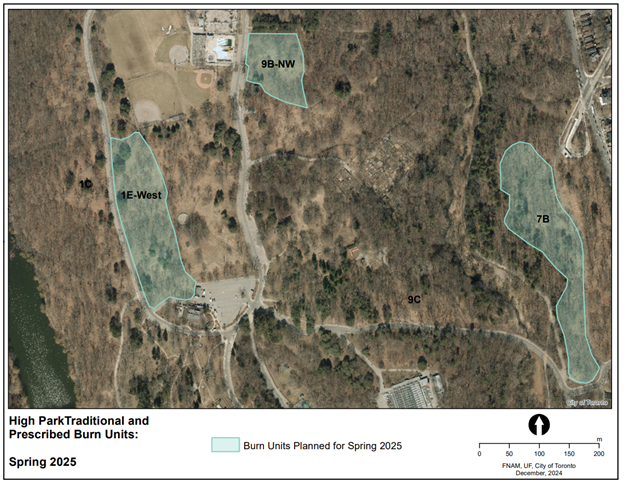

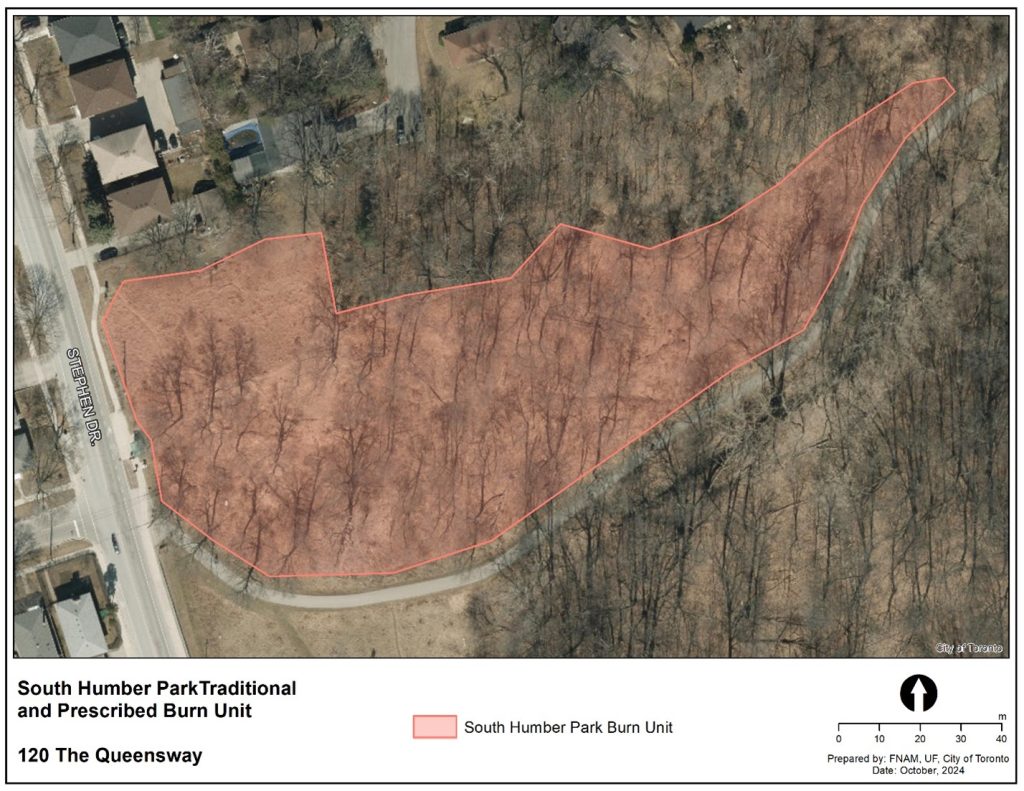

High Park will be temporarily closed to vehicles on the day of the prescribed burn, and will be re-opened once the fire is complete. Please refer to the maps below for exact burn locations within each park planned for this year.

During prescribed burns:

While we aim to provide fully accessible content, there is no text alternative available for some of the content on this site. If you require alternate formats or need assistance understanding our maps, drawings, or any other content, please contact Karen Sun at 416-392-1891.

The City uses a variety of different ways to communicate traditional and prescribed burn plans and preparation.

Updates on the traditional and prescribed burn will be posted on the City’s social media channels as they become available.

Notices will be:

News releases will be issued about upcoming traditional and prescribed burns. If you have additional questions call 311 (416-392-2489 from outside the city limits).

A traditional and prescribed burn is a deliberately set and carefully controlled fire. It burns low to the ground and consumes dried leaves, small twigs and grass stems but does not harm larger trees. Fire-dependent ecosystems, such as Toronto’s rare Black Oak savannah, contain prairie plants that respond positively to burning, and that grow more vigorously than they would in the absence of fire. Species that are not adapted to these ecosystems can be reduced with repeated use of fire. The use of fire is part of the City’s long-term management plan to restore and protect Toronto’s rare Black Oak woodlands and savannahs.

Traditional and prescribed burns are:

The traditional and prescribed burn will:

The City of Toronto hires a Fire Boss and their crew who are experienced in high-complexity burns. The Fire Boss and his crew are in charge of the technical aspects of setting and controlling the fire. City staff are responsible for determining the goals and objectives of each burn unit and preparing each site for the planned burn.

The Fire Boss along with City staff, leading experts and members from the Indigenous community visit the site six months before the burn to assess the area and review numerous factors, including the type of fuel on site (leaves, twigs, and stems), topography, proximity to public and private infrastructure.

During the winter months, City staff will prepare burn sites by clearing the majority of woody invasive species in the understorey. This helps to increase the light, space and availability of nutrients required for the native seedbank to germinate and flourish after the burn is completed.

Once the snow has melted and weather patterns begin to consistently warm, City staff will begin daily monitoring of on-site ground conditions and report this to the Fire Boss who will determine when the site is ready. The Fire Boss makes this decision by assessing the dryness of the site as well as forecasting the expected temperatures, humidity levels and wind patterns to support a slow-moving fire with high smoke lofting.

Since weather is difficult to predict with certainty, the day of the burn is selected within 24 to 48 hours of the anticipated ideal conditions in spring. On the day of the burn, the Fire Boss will determine the appropriate time to set the fire so that it will remain under control and progress across the site at a walking pace, to ensure safety and the desired effect of setting back undesirable plants.

The Black Oak savannah habitat is extremely rare. It is estimated that less than three per cent of the original pre-settlement cover of prairie and oak savannah ecosystems remain in Ontario.

In Toronto, Black Oak savannah remnants can be found in South Humber Park, Lambton Park and High Park. High Park contains approximately 29 hectares of fragmented savannah and oak woodland, and is the most significant area of remnant prairie and savannah plant communities in the Toronto region. High Park has a healthy population of uncommon and rare savannah plants. This was recognized by the Province of Ontario when it was designated an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) in 1989. South Humber Park, Lambton Park and High Park are all classified as Environmentally Significant Areas (ESA) in the City of Toronto’s Official Plan.

Savannahs are defined by The Ecological Land Classification as widely-spaced open-crowned trees that provide between 25 to 35 per cent canopy cover. These trees are surrounded by a sea of prairie plants including tallgrasses like Big Bluestem and Canada Wild Rye, forbs such as Hairy Beardtongue, Wild Bergamot and Black-eyed Susan, and low-lying shrubs such as Northern Bush Honeysuckle and New Jersey Tea.

What is unique about the Black Oak savannah and one of the reasons why it is so significant, is the incredible diversity of flora and fauna that it supports. It offers a unique array of shade to full sun in sandy soils that appeals to many different species all in one area. This habitat has one of the highest diversity counts of Ontario’s ecosystems.

Savannahs are fire-dependent ecosystems, which rely on burning the landscape in order to maintain them. Fire benefits native plants and helps to sustain a unique habitat for the wildlife that depend on this ecosystem.

Before European settlement, the landscape was defined by Indigenous Peoples’ use of traditional burns to manage the landscape, coupled with naturally-occurring wildfires. Indigenous Peoples would use fire to clear the land for agriculture, to rejuvenate the quality and quantity of forage and medicinal plants, and to attract wildlife. This use of fire also helped to regenerate and maintain savannah habitats.

Traditional and prescribed Burns are designed to echo these historic controlled and natural fires and benefit native plants and animals by reducing invasive/exotic plants and grass, stimulating native plant regeneration, restoring wildlife habitat and returning nutrients to the soil.

Toronto’s magnificent oak trees are some of the largest and longest-living trees in the city and their acorns provide food for over 100 species of birds and mammals. One species of oak, the Black Oak has adapted its bark so it can withstand fires which helps it to thrive in fire-dependent ecosystems such as High Park’s Black Oak Savannahs and Oak Woodlands and are a key component to the preservation of these magnificent ecosystems. In fact, Black Oaks need occasional fires to ensure their survival and to promote the successful regeneration of new Black Oaks. As such, they have adapted their leaves to help encourage a low-travelling burn with their thicker leaves that take longer to decompose and the natural curling of the leaves that help fire travel from leaf to leaf.

In 1995, an evaluation of the oaks in High Park determined that the trees were nearing the end of their life expectancy. Furthermore, it revealed a concerning discovery: there were no young oaks or oak seedlings regenerating to replace them. This was due to several key factors including but not limited to the suppression of fire resulting in a build-up of leaf litter which impeded acorns from reaching the soil; excessive population of squirrels eating the acorns; and herbivory on the seedlings that could take root.

Following the reintroduction of fires to the landscape, natural Black Oak regeneration has once again been observed. Coupled with targeted re-planting efforts of locally sourced Black Oaks and improved conditions for associated savannah species to thrive, the longevity of this important ecosystem is very promising.

The burn will temporarily produce large amounts of smoke in the park and the surrounding community. Every precaution is taken to limit the spread of smoke. Under ideal weather conditions, the smoke from the burn will rise upwards and will not affect park visitors or surrounding neighbourhoods. However, it is possible that weather conditions could change, and some smoke will linger in the park.

If people are sensitive to smoke or poison ivy, they are advised to take precautions such as not entering the park during the burn and if they live in the nearby community, they should close all doors and windows.

Parks will be closed to vehicles on the day of the burn. In addition, sections of the park being burned will be closed to cyclists and pedestrians in order to protect park visitors and to reduce the risk to visitors and their dogs. It will be safe to walk through areas of the park that are not being burned.

Traditional and prescribed burns are scheduled at a time of year when birds are not nesting and before hibernating animals emerge. Burn sites are intentionally planned to be small and patchy to allow for wildlife and insect refuge areas, and to preserve unburned areas for overwintering insects, such as pollinators. Large cavity trees that may be home to wildlife are also protected from burning by creating a fire break at the base of the tree.

Immediately prior to burning a site, staff will perform a wildlife sweep. This is achieved by lining up staff the length of the site and walk in a line across the site. Through this method, they create ground vibration and movement that encourages wildlife to return to their underground nests safe from the heat of the fire or to leave the site. This also gives the opportunity for staff to observe for any wildlife, people or dogs in the area before ignition.

Post-burn, the continued management of the burn sites is important. Invasive species are opportunists and may attempt to grow into a newly burned site before the native plants in the seedbank have a chance to grow and fill the space. City staff will monitor the burn sites and plan for the management of invasive species as required. Monitoring the sites is an important way of determining both the short-term and long-term success of a site.

The success of the burn is determined by City staff trained in ecosystem management, the Fire Boss, and leading experts from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA).

City staff have established goals and objectives for each unit that is burned, monitored burned areas over many years, and determined the effects of fire on achieving the goals. The main desired effect is to see greater populations of prairie plants and the regeneration of fire-dependent Black Oaks, while at the same time seeing reduced growth and decreased populations of invasive plant species.

According to the TRCA 2019 High Park Biological Inventory Report, High Park has 75 naturally occurring plant species of regional conservation concern with 23 of those being regionally rare. Most of these 23 plants are associated with the oak woodland and savannah habitats in High Park. The report also noted that the populations of some of these rare species are recovering in the burned areas after a steep decline through the 20th century. Some of these species include Wild Lupine, Canada Hawkweed and Cylindrical Blazing Star.

“A responsibility for a cleansing burn by all Native Peoples”

Biinaakzigewok Anishnaabeg is the Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) name for the traditional and prescribed burn shared by Indigenous Elder Henry Pitawanakwat.

The cleansing fire or burn had been used by Indigenous Peoples long before colonization. The Anishnaabeg’s relation to the world has much to do with balance, both within oneself, as well as in everything around us. In Black Oak Savannahs, the burn allows more diversity among native plants and berries to thrive. In particular, the blueberry and strawberry, or the heart berry, enjoy these burns to make space for themselves.

These fresh spaces with more open grazing allow animals like deer to frequent more often. This in turn allows Indigenous Peoples to hunt and be able to provide for their community. When this all works together, there is balance. From the burn to the berries to the grazing to the hunting, this cyclical effect empowers every part of the chain of nature. This is reciprocity from start to finish.

The practice of controlled burns was wiped out when colonization hit the great lakes. It created major imbalances and we can see those effects with the degradation of these Savannah ecosystems. The City of Toronto has had these burns for the past two decades and has slowly been growing a relationship with the Indigenous community. There is a growing movement of empowerment to the original caretakers of these lands with Indigenous Peoples and ceremony being included in the planning and execution of these burns. High Park Black Oak Savannah burns have created a great opportunity for two-eyed seeing, and the future is bright for both the Anishnaabeg and everyone who now calls these lands home. We will witness and be part of the seventh fire, it is the only way forward.

Niikaniganaw – All our relations