WWI Commemoration

The year 2014 marked the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. In commemoration, the City of Toronto organized various events, exhibits and initiatives to honour the service and sacrifice of the many Canadians who fought for their country. This page will provide you with an overview of planned initiatives from 2014 to 2018, as well as resources to learn more about the history of the war.

In the fall of 2014, 12 “pop-up museum” events were held across the city, where descendants of family members who lived during the war told their stories.

These stories are oral histories, in most cases passed down through two, three and sometimes even four generations, accompanied by a number of keepsakes. At other times, the stories evolved when keepsakes were found unexpectedly during the clearance of attics, basements, closets and trunks, inspiring those who found them to search for more information about the original owners and their experiences. All the storytellers wished to honour and share the experiences of people whose lives were deeply affected by the First World War.

Many of these stories and photos can be viewed through the Canadian Encyclopedia’s Your Canada map.

Short Documentary Films

Ten short documentary films were produced as a result of the Toronto’s Great War Attic program. They can be viewed on the City of Toronto Historic Sites YouTube channel.

Trench Art – Wayne Reeves

“These trench art examples were acquired by a Toronto collector in the US. They are German 77 mm artillery shells casings likely tooled by a French artisan to mark two 1918 battles involving the American Expeditionary Force: Chateau Thierry and the Argonne Forest.

Save for the battle names, the artwork is identical – revealing that some trench art pieces were created using templates, and are not “one of a kind” pieces. Both works are inscribed “1914-18”; if the template had been made exclusively for the American market, then “1917-18” would have been appropriate. Perhaps trench art exists with an identical base pattern but which is inscribed with the names “Ypres” or “Vimy,” which is more closely tied to the Canadian experience?”

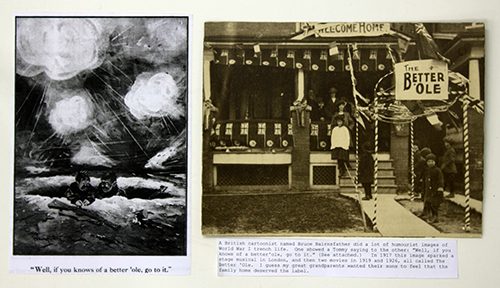

The Better ‘Ole – Craig Heron

“The photo was probably taken in 1919 when Canadian troops were arriving home after the end of the war. The house done up in bunting was on Concord Ave in Toronto, and was owned by my great grandparents, William and Maggie Gardner, who were shopkeepers.

“The Better ‘Ole” refers to a famous cartoon by British artists Bruce Bairnsfaher, who did many cartoons about “Old Bill” and his friends serving in the armed forces. One of his cartoons showed Old Bill saying to his mate: “Well, if you knows of a better ‘ole, go to it.” In 1917 this image sparked a stage musical in London, and then two movies in 1919 and 1926, all called “The Better ‘Ole.” I guess my great grandparents wanted their two sons who had served overseas (George and Gilbert) to feel that the family home deserved the label.”

A Toronto Perspective on the War

During the First World War, Toronto was English-Canada’s largest city and the headquarters for a military district spanning Central Ontario. With a largely British population, Toronto eagerly mobilized for war in 1914 for King and Empire.

Toronto became a focal point for recruiting, training and sending men and women off to the war and then raising funds to support both the military overseas and the families left behind. The city’s productive energies were unleashed, enabling women to assume new roles in Toronto society.

The war brought long-simmering debates over alcohol and suffrage to a head. Prohibition forces won the day in 1916, to the dismay of soldiers and returned men. Nurses and women related to soldiers got the federal vote in 1917, enabling conscription to be implemented.

As the war ground on, Torontonians became less tolerant of ethnic minorities. Anti-German sentiment found many expressions. The registration of enemy aliens was followed by their internment at Exhibition Park. In 1918, veterans attacked local Greeks for not doing their ‘bit.’

As the war neared its end, Torontonians grimly faced food and fuel shortages and then the Spanish flu pandemic. They celebrated victory when Armistice Day came in 1918, but they also grieved for the dead who would never return to their city. Toronto now faced the task of remembering those who had served and those who had sacrificed.

Mobilizing for War

After war was declared in August 1914, Torontonians rushed to enlist. Later, Toronto’s militia regiments, schools, clubs and businesses assisted with recruitment. As the number of volunteers declined, social pressure techniques encouraged “slackers” to join up. When even these efforts faltered, conscription followed in 1918.

By war’s end, over 45,000 Torontonians had served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force or with the British Army. More than three-quarters of all eligible young men in the city had volunteered to serve.

Toronto was an important training centre. Exhibition Park became a winter training camp, housing 10,000 troops in 1915-16. The University of Toronto hosted the Royal Flying Corps in Canada. Torontonians encountered the military often – on route marches and other exercises, at parades, demonstrations and model camps.

Tens – perhaps hundreds – of thousands of soldiers and nurses passed through the city during the war. As a railway hub, troops were fed into Toronto and then dispatched by train to Quebec and Nova Scotia before boarding ships for England. Time and again, Toronto was the scene of poignant leave-taking.

City Government Steps Up

City Hall was Toronto’s patriotic epicentre. Ever-present at the recruitment and fundraising rallies, military reviews and parades, armistice celebrations and remembrance services was “The Soldier’s Friend” – Tommy Church, on the Board of Control in 1914 and mayor of Toronto from 1915 to 1921.

City Council’s support was both symbolic and tangible. Municipal horses were donated to the military. To encourage enlistment, all Toronto residents on active service were provided with life insurance. In 1915, the City assumed the full risk of insuring the lives of her soldiers. This cost $4.4 million, part of Toronto’s $13 million in war expenditures.

Though many municipal workers were on active service, Toronto’s infrastructure expanded during the war. The Island Filtration Plant became the world’s most advanced water treatment facility, while the Bloor Viaduct spanned the Don Valley. The Toronto Civic Guard was created to protect the City’s water supply.

Funding the War Effort

Torontonians contributed huge amounts of money and time to the war effort. Tag days – supporting causes as varied as comfort huts, Belgian refugees and wounded war horses – became a common feature of street life. Khaki Day in 1915 was unprecedented, with 2,500 tag sellers raising $34,000 for the Citizens’ Recruiting League.

A more significant ongoing initiative was the Toronto and York County Patriotic Fund, established in August 1914. In four annual campaigns, $9.5 million was subscribed to provide aid to the dependents of soldiers. About 20,000 families (some 50,000 individuals) were given relief.

Even more impressive was Toronto’s commitment to the federal Victory Loan campaigns which raised money for Canadian industries and agriculture. Toronto set a “world’s record” in 1917 with 126,390 subscribers – over one-quarter of the city’s population. In 1919, Torontonians subscribed nearly $145 million, more than one-fifth of the national total.

The Industrious City

Torontonians enthusiastically set to work as volunteers and wage labourers to provide materiel for the war effort.

With men away on service, women’s work became pivotal. It was initially a patriotic extension of the domestic sphere – knitting and sewing socks and other “comforts” for soldiers. Non-traditional canvassing, recruiting, clerical and factory roles followed. By the end of 1916, Toronto employed 2,500 of Canada’s 4,000 female munitions workers.

Industrial activity burgeoned after the Imperial Munitions Board, led by Toronto businessman Joseph Flavelle, formed in 1915. Locally, the IMB did more than award ammunition and shipbuilding contracts. Three of its seven “national factories” were in Toronto. British Acetones Toronto Limited was the Empire’s largest provider of the explosive cordite. British Forgings Limited became the world’s biggest electric steel plant. Canadian Aeroplanes Limited built 2,951 aircraft.

By 1917, wartime scarcities spurred thrift and conservation campaigns at home. Cooks substituted or reduced foods so more could be sent overseas. Supplies were augmented by vacant-lot and home gardens and paper and scrap metal drives.

Resolving Old Issues

Toronto had been a national leader for women’s suffrage since the 1870s. In 1914, women who had been pursuing the vote set aside their campaign to focus on supporting the war effort.

The wartime contributions of women were recognized by Queen’s Park and Ottawa in 1917. Women who were British subjects and who were either in the armed forces or who had male relatives on active service first voted in the divisive federal election of December 1917.

Local options for limiting the sale and consumption of alcohol in Canada date to the 1860s, but the prohibition movement surged during the war. Drinking was depicted as a wasteful, inefficient use of scarce resources.

After a vigorous Toronto campaign by the “drys,” Ontario enacted a prohibition law in 1916. Federal action followed in 1918. Many veterans opposed prohibition, seeing it as an unjust restriction of the liberties for which they had fought.

Loyalties in Question

In 1914, over 85% of Torontonians were of British stock. Immediately after the war began, attention turned to those who were not native-born Canadians or naturalized immigrants. Though tolerance was initially preached for Canada’s enemy aliens, life became difficult for many of Toronto’s ethnic minorities.

Across the country, enemy aliens – Germans, Austrians, Hungarians and Turks – were required to register with the authorities. Some were placed in internment camps. A Toronto “receiving station” set up in Exhibition Park housed internees in 1914-16.

Anti-German sentiment rose after the passenger ship Lusitania was sunk in 1915. The dead included 86 Torontonians. Mayor Church ordered the closing of German clubs, and the City renamed streets with German-sounding names.

Other foreign-born Torontonians experienced prejudice. In August 1918, anti-Greek riots shook the city. Veterans demanded that local Greek men either enlist with the Canadian forces or return to Greece to fight with the army there.

The End of the War

Toronto celebrated the armistice of November 1918 which ended the fighting, and the peace treaty of June 1919 which officially ended the war. But for some Torontonians, the war was over long before those events.

Wounded veterans began returning to Toronto in 1915. Military hospitals were opened to care for these “returned men.” Many were embittered by their experiences overseas and disenchanted with their prospects back home. These feelings were shared by some of those soldiers who returned en masse following demobilization in 1919.

There were also those who would never return to Toronto – the 4,904 soldiers and nurses who had died on active service during the war. Their loved ones would remember their sacrifice in public by wearing medals and raising service flags.

Grief would also be expressed collectively at the memorial plaques and monuments erected across the city. The most important of these was Toronto’s permanent cenotaph, unveiled at (Old) City Hall in 1925.

Books

- Cook, Tim. At the Sharp End: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1914-1916. Volume 1. Toronto: Viking Canada, 2007.

- Cook, Tim. Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1917-1918. Volume 2. Toronto: Viking Canada, 2008.

- Glassford, Sarah and Amy Shaw, eds. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland During the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

- Granatstein, J.L. Hell’s Corner: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Great War, 1914-1918. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2004.

- Miller, Ian Hugh Maclean. Our Glory & Our Grief: Torontonians and the Great War. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

- Morton, Desmond. Winning the Second Battle: Canadian Veterans and the Return to Civilian Life, 1915-1930. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987.

- Morton, Desmond. When Your Number’s Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War. Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1993.

- Morton, Desmond. Fight or Pay: Soldiers’ Families in the Great War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004.

- Nicholson, G.W.L. Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1964.

- Taboika, J. Victor. Military Antiques and Collectibles of the Great War: A Canadian Collection. Ottawa: Service Publications, 2007.

- Vance, Jonathan F. Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning, and the First World War. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997.

- Wilson, Barbara M. Ontario and the First World War, 1914-1918: A Collection of Documents. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1977.

Websites

- Historica Canada

- Canadian War Museum

- Library and Archives Canada

- National Film Board

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Archives of Ontario

- Canadian Great War Project

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- The Canadian Letters & Images Project

![Wounded veterans at Yonge and College, 1916 [City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 736]](https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/95ea-edc-GreatWarBanner.png)